コランダムの高温低圧(HT+P)処理について<日本語><中文><English>

<日本語版↓>

《こちらはwww.lotusgemology.comのオンライン記事から許可を得て転載しています。オリジナルは2019年2月4日にアメリカのツーソンで開催されたGemstone Industry & Laboratory Conference(GILC)にて公表されました》

==================================================

【 Sapphire Squeeze • Corundums treated with high temperatures and low pressure(HT+P)】

Sapphire(サファイアへの圧力)・高温低圧(HT+P)処理コランダム

2019年2月26日:高温低圧(~1kbar)処理サファイアが最初に市場に現れたのは2009年で、2016年以降頻繁に見られるようになった。今回の記事ではそのプロセスを詳細に検証し、当該処理に個別の情報開示が必要となるか否かについて検討する。

今回の記事の内容について以下の各関係機関にご協力をいただいた:中央宝石研究所(CGL、日本)、CISGEM(イタリア)、German Gem Lab(DSEF、ドイツ)、Dunaigre Consulting(スイス)、Gemological Institute of America(GIA、アメリカ)Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand(GIT、タイ)、GJEPC–GTL(インド)、Gübelin Gem Lab(スイス)、Hanmi Lab(韓国)、ICA Lab(タイ)、Lotus Gemology(タイ)、Swiss Gemmological Institute(SSEF、スイス)。

考察

高温低圧で加熱されたサファイア(~1kbar;以下「HT+Pサファイア」と呼ぶこととする)が最初に市場に登場したのは2009年で、2016年にはより一般的に見られるようになった。2018年後半、Gem Research Swisslab(GRS)が、高温低圧の処理を施された石は耐久性に問題があるという研究を発表した(Peretti et al., 2018, 2019)。その後American Gem Trade Association(AGTA, 2018)もすぐにそれに続いて、熱および圧力を伴う処理を受けたすべてのサファイアに対してHPのカテゴリーにおいて個別の情報開示を必要とするとの見解を発表した。さらにAGTAは、すべての処理同様、消費者の手にわたる書類のいずれも単に記号だけでなく「明確な言語による」情報開示(例えば、熱および圧力を伴う処理をされたサファイア、など)が必要であると述べている。

AGTAが個別の情報開示を要求する理由は、この処理が石の品質を変えるからであるが、一方でこの処理は既に「情報開示」が行われており、個別のカテゴリーになっていないだけという問題の核心をAGTAは回避している。では、HT+P処理により生じる変化が従来の加熱処理の場合よりも程度が大きい場合はどうなのか、という疑問が当然ある。今回の記事では、加熱プロセスに低めの圧力を加えることが、業界関係者および消費者に個別の情報開示をしなければならないほどの結果をもたらすのかどうかという重要な問題に対して取り組んでみる。

年表:加熱の歴史

処理との関連におけるサファイアの加圧加熱処理の概要が分かるように、コランダムの加熱処理の歴史を振り返ってみよう。

およそ紀元1045年:ルビー/ピンク サファイアの青色みを除去するための低温加熱

偉大な博学者Beruni(生:紀元973~没:1050)は、50ミスカール(1ミスカールは現代の4.25gに相当、≒212グラム)の金を溶かすために設計された溶融炉でルビーを加熱する工程について記述している。金は1064℃で溶けるため、その溶融炉は空気中で1100℃以上の温度に達する能力があることが分かる。また、これは宝石処理業者がこのタイプのルビーやピンク/パープル サファイアに今日行っているのと基本的に同じプロセスであることから、Beruniの述べた工程が有効であることも分かる。(Beruni, 1989; Hughes et al., 2017)。初期の加熱処理(www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/lab/enhancements#gemtreatments)も参照。

1916年:青色を淡色化させる低温(800–1200℃)加熱

クィーンズランド(オーストラリア)産の暗青色(玄武岩起源)サファイアを、色を明るくするために低温で加熱処理。このプロセスは後にすべての暗色ブルー サファイアの加熱に適用され、今日でもそれが継続している。これらの石は生成されてから地表に到達するまでの間に玄武岩質マグマ内ですでに自然界における加熱を経験しているため(著者不明、1916)、この処理を看破することは難しい。

1966年:処理の高温化

GIAのRobert Crowningshield は、タイ産であるとされるが弱い鉄スペクトルを示し、短波紫外線に対し珍しい白濁蛍光の反応を見せるサファイアについて報告している。今でこそ、この蛍光は一般的にギウダ タイプの変成岩起源サファイアを高温で加熱したものであると分かる(Crowningshield, 1966)。今だから言えることは、これは低鉄含有変成起源サファイアを高温で加熱する初期の試みであったと思われる。

およそ1975年:ギウダの時代

スリランカ産のギウダ(geuda)サファイアを青色に変えるためにディーゼル炉(1500℃)が用いられる。酸素の添加により、ルチルを溶解させるのに必要となるより高い温度に達することができる。このプロセスではたいてい還元雰囲気において水素拡散を伴う。1970年代後半、こうして処理された石が大量に市場に流入し、バイヤーの多くは買い付けた石が処理石であることを知らなかった。このため、1980年代になると業界はこれを「伝統的な」加熱処理であると称したが、当時その「伝統」は20年も経っておらず、また、それまでに行われていた加熱の結果とはまったく異なるものであった。ニューヨークにあるAmerican Gemological Laboratories (AGL) はこの処理に関する情報開示を始めた最初のラボで、他のラボがそれに倣い始めたのは1980年代の後半になってからであった。

- これはこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を添加するか? いいえ。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? そういう場合もある。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? いいえ。

1980年:チタン格子拡散

チタン格子拡散(当時は「表面拡散」と呼ばれた)処理されたサファイアが市場に入ってきた。当初、ユニオン カーバイド社から特許権を買い取った大手スイス企業が適正な情報開示を行わずにこれらのサファイアを販売したが、処理はすぐに看破され市場にはほぼ浸透しなかった(Nassau, 1981)。

- これは新しい処理法だったのか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? はい。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? はい。

1980年代初期:電気炉

電気マッフル炉が導入され、雰囲気と温度制御の精度が高まった。酸化雰囲気での加熱により多くのスリランカ産サファイアが淡青色から鮮やかなイエローやオレンジに変わり、こうした素材が市場にあふれるようになった(Keller, 1982)。

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? いいえ。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? いいえ。

1980年代半ば:フラックス修復

加熱プロセスの途中でフラックスを添加することでひび割れが修復し、ひび割れていた石が超極微量の合成コランダムで隙間をふさがれる。1991年にモンスーでルビーが発見されると、この素材が市場に流入した(Hughes et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2004)。

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? いいえ。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? はい。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? はい。

1990年代半ば–2001年:ベリリウム拡散

ベリリウム拡散処理コランダムは徐々に市場に浸透していった。このプロセスの権利は後に売却され、2001年までにはこの素材が市場にあふれることとなった。ジェモロジストは2002年初頭には原因を看破した(Emmett et al., 2003)。

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? はい。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? はい。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? はい。

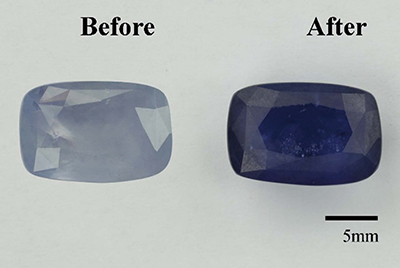

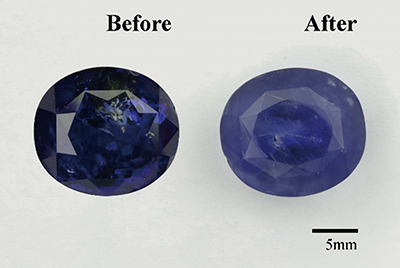

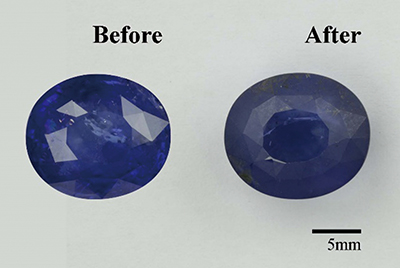

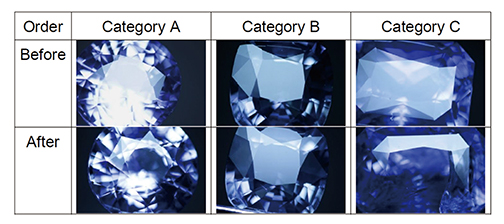

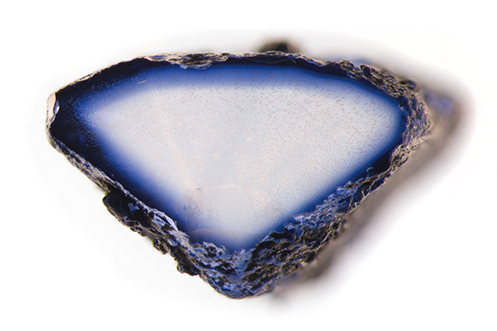

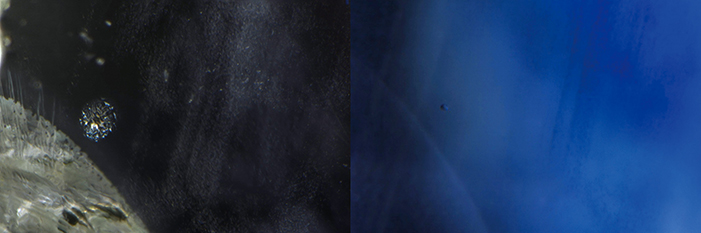

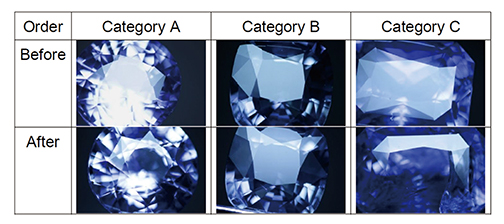

下:マダガスカル産サファイアのベリリウムを伴う高温加熱(1700℃+)の前(左)と後(右)。ギウダの加熱処理は加熱(H)に対する情報開示のみが必要であるが、Be拡散処理の場合は発色因子(Be)が外部から石の内部へと導入されていること、また、石を再研磨すると場合によって色が失われる可能性もあることから、個別の情報開示が必要となる。Hughes et al., 2014より。写真:Wimon Manorotkul;試料および加熱:John Emmett

2000年–2003年:長時間の加熱で高度な制御

加熱時間を長くすることで処理業者は仕上がりの色をより上手く調節できるようになった。処理業者は大がかりな実験を行い、加熱処理プロセスを改良した結果、いわゆる「Punsiri(プンシリ)」の危機に至り、当初はスリランカの処理業者による石は問題を生じかねない商品であると疑われたが、これは後になって標準的な加熱処理を高度に変化させたものであることが示された。

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? いいえ。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? そういう場合もある。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? いいえ。

2003年:暗青色サファイアを明るくするベリリウム拡散

ブルー サファイアにベリリウムを拡散させて色を明るくする。この処理が施された石は鑑別するのに高度な装置が必要であるため、市場にゆっくりと浸透した(Emmett et al., 2003)。

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? はい。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? そういう場合もある。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? はい。

2009年–現在:圧力を伴って加熱されたサファイア(HT+P)

圧力+高温により処理されたブルーサファイアが出現(Choi et al., 2014a, b)。これらの石はゆっくりと市場に現れた。現在の状況は以下の通り:

- この処理はこれまでのプロセスに改変を加えたものか? はい。

- この処理では外部から発色因子を導入するのか? いいえ。

- この処理は石のかなり大きなひび割れを再結晶化/修復するか? そういう場合もある。

- この処理は耐久性に問題があるか? 我々の見る限りでは、問題は無い。

- 個別の情報開示(「加熱」だけでは不足)が現在求められているか? これは喫緊の課題である。

以上のように、処理の情報開示についての宝石業界における歴史はどう見ても公平とは言えず、ジェモロジストが新しい処理を最初に看破する前にその処理が施された石がどの程度市場に浸透してしまっているかによって状況が変わっている場合が多い。市場にすでにたくさん流入してしまっている場合(ギウダ サファイアの高温加熱処理)は、業界は「伝統的」として見過ごす傾向があり、新しい処理が初期の段階で見つかった場合(ベリリウム拡散)は、業界はより批判的になった。これは意外でも珍しくもないことで、人間はまず自分の利益のことを考えるものなのである。

とは言え、米連邦取引委員会(FTC)ガイドラインおよびAGTAの情報開示ポリシーによると、現在の基準は以下のとおりである(AGTA、日付不明):

処理の詳細については以下の場合に情報開示されなければならない。

- 処理が恒久的ではなく、その効果が時間とともに無くなる;または

- その処理を施したことによる利点を継続させておくために宝石に特別なケアが必要となるもの;または

- 処理が宝石の価値に重大な影響を及ぼす。

新しい高温+低圧(HT+P)処理に関しては、上記の情報開示条件のいずれかに当てはまるのか?

これは重要な疑問であり、今回の記事でその答えを探る。

圧力をかける

ダイヤモンドの処理業者は、1990年代以降は色を改良するために高温高圧を用いてきた。そのため、コランダムの加熱業者がルビーやサファイアの加熱に圧力を導入するであろうことは時間の問題であった。実際に1997年から、ドイツの加熱炉メーカーLINNがコランダム加熱用の低圧のオートクレーブ(最大25 bar)を販売した。何台かはアジアに販売された。同様に、トルマリンの加熱処理に携わっていた人々はずいぶん前から圧力を伴う加熱を行っており、流体で満たされたネガティブ クリスタルを破裂させることなく色を改変させていた。この処理(温度700℃以下、圧力0.5–1.5 kbar)は今日まで続いており、基本的には看破不可能である。

サファイアのHT+P処理では、使われる圧力(~1kbar)はもっと低い。サファイアが地中で成長するときの圧力と比較すると、この処理で使われる圧力は、宝石内部の流体で満たされたネガティブ クリスタルの破裂を防ぐには全く不足である。実際に、この処理が施されるサファイアは既に高温で加熱されているものが多い。そうすると疑問が生じる。なぜHT+P処理が行われるのか?その答えは、処理がはるかに短時間で済み、30分足らずで完了するからである。

しかし欠点もある。加熱装置は従来の処理用加熱炉と比較して非常に高額である。また、多くの場合一度に処理できるのは一石だけである。さらに、色の改変を生じる変化が急激に起こるため、制御はその分難しくなる。この処理によって生じる結果が多様であるのはそのためである。

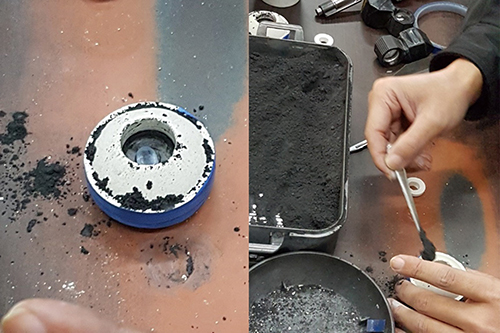

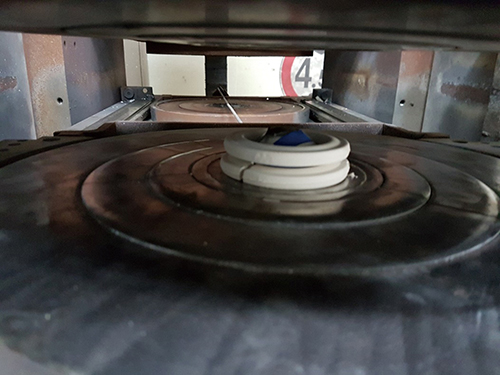

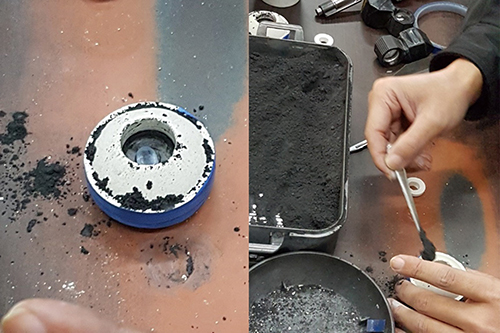

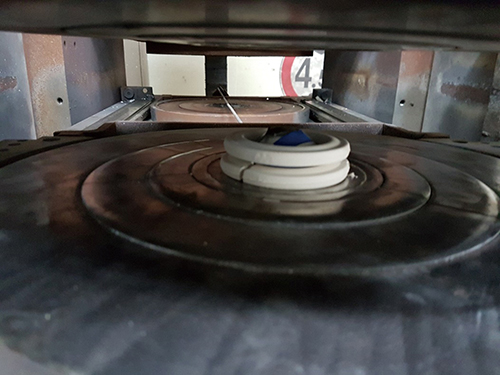

サファイアへの圧力:HT+P処理法

以下に述べる情報は、主に韓国のHanmi Lab、タイのGIT、GIAによる韓国の加熱処理施設訪問に基づくものである。

密封された容器はその後、加熱/加圧機に入れられる。写真:GIT

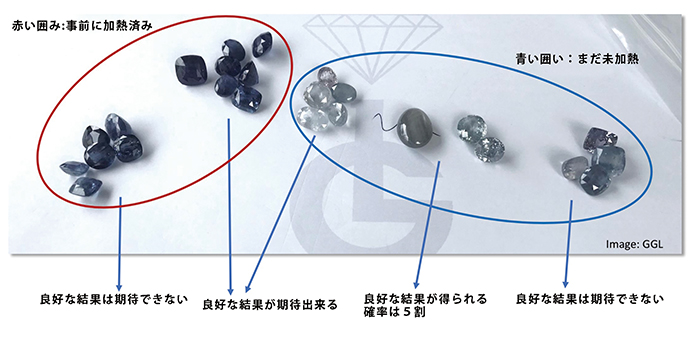

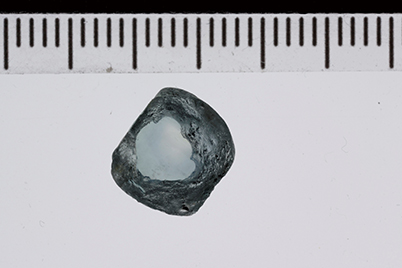

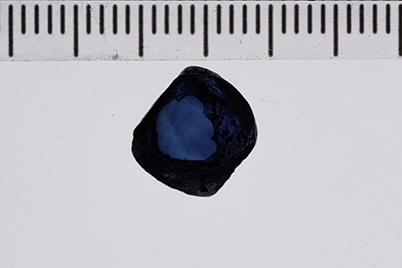

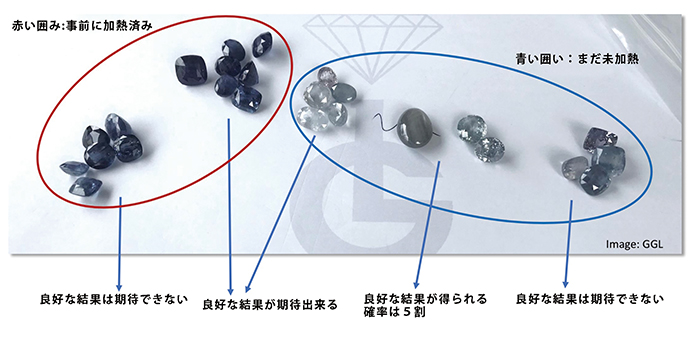

HT+P処理の出発材料

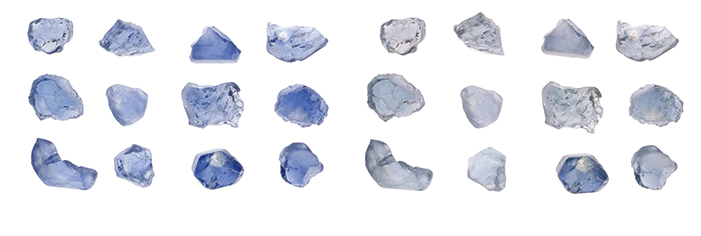

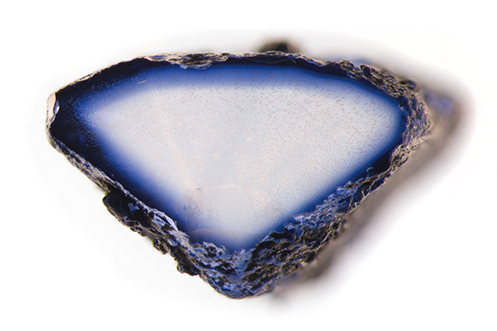

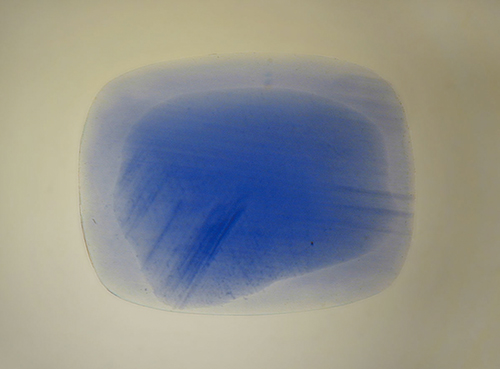

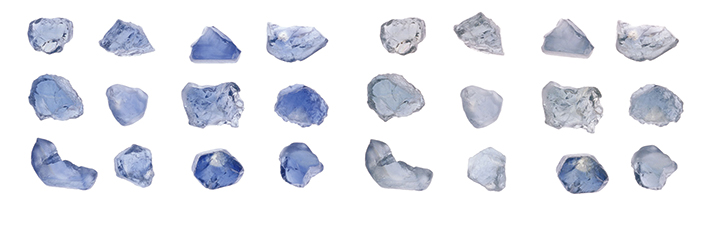

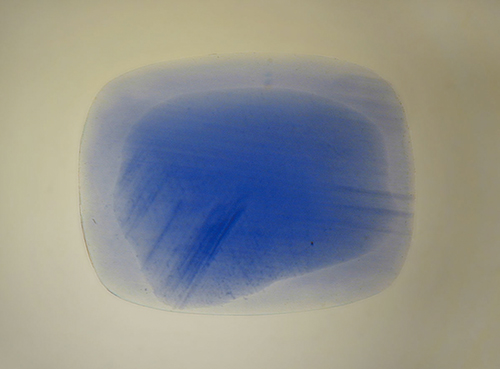

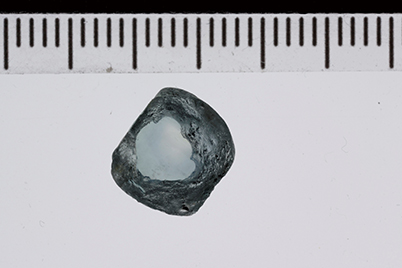

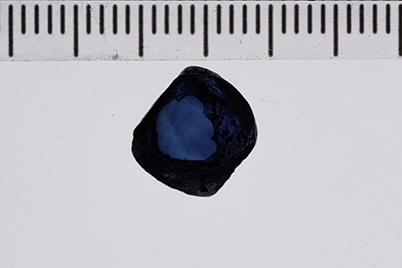

下:同じ石を、HT+P処理した後。従来型の加熱と同様、出発材料の化学組成の違いによって結果はまちまちである。Choi et al., 2018より。写真:P. Ounorn

HT+P処理サファイアの鑑別

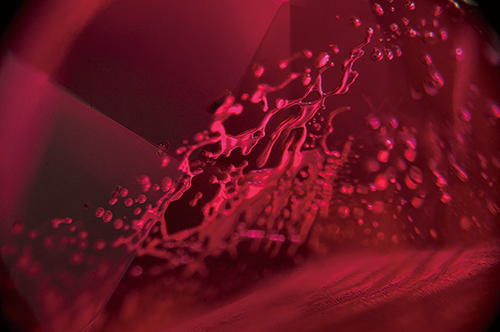

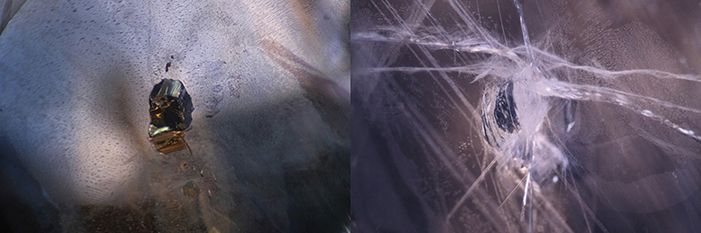

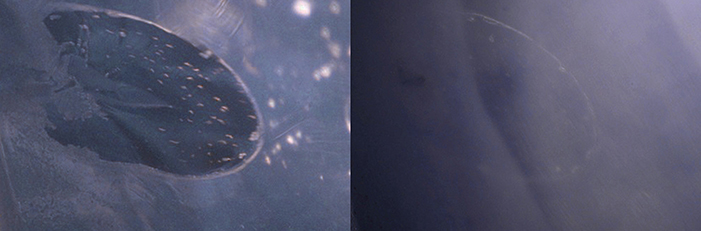

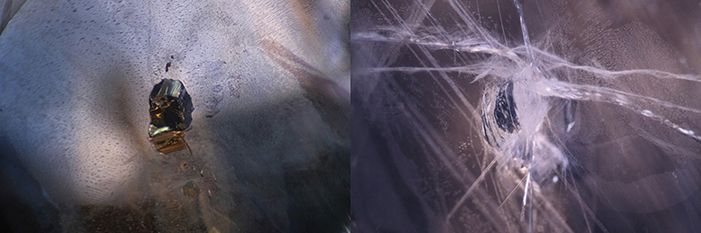

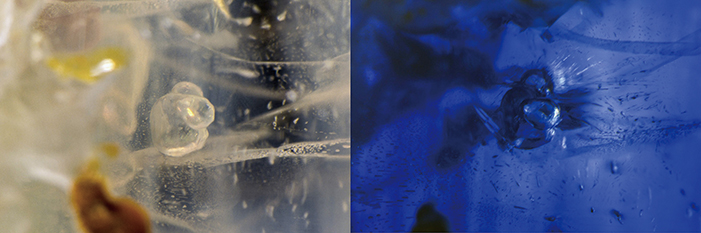

インクルージョン

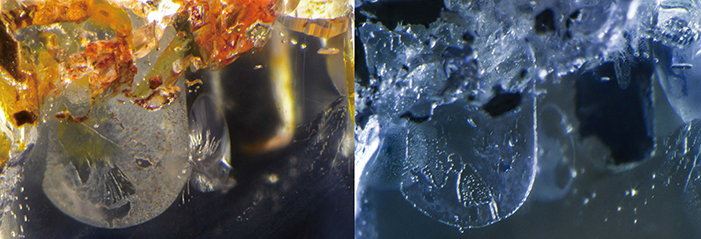

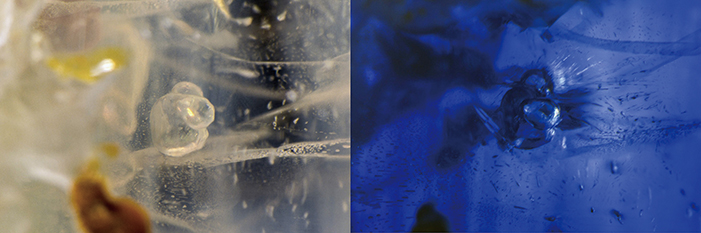

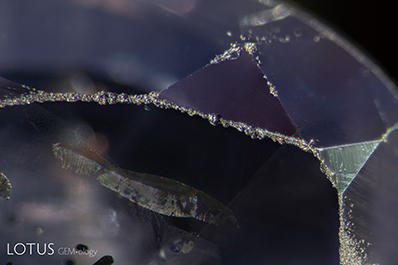

HT+Pサファイアの顕微鏡観察のまとめ

HT+P処理サファイアに観察される特徴は、「伝統的に」高温加熱されたサファイアにみられるものと類似していた。

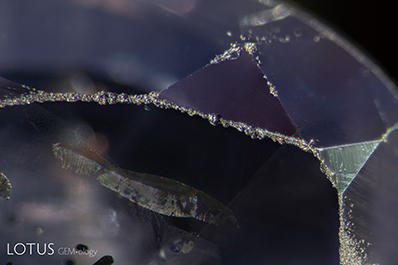

- 修復されたひび割れの表面の粒度にわずかな違いが見られた。しかし、似たような特徴は従来の加熱サファイアにも見られている。

- 時にひび割れやキャビティ中の表面近くにグラファイトの蓄積が見られることがある(グラファイトで充填された容器からの残留物)。

多くの場合、顕微鏡観察は通常の加熱処理からこの処理を識別するのに十分な証拠を呈してはくれなかった。上に挙げた画像から、この処理の結果生じる変化のタイプは、圧力を伴わない高温加熱処理の場合に予想される結果と実質的に同じであったことが分かる。

その他の検査

HT+P処理サファイアにさまざまな宝石学的検査を行った。以下にその検査の例を挙げる。

紫外線(UV)蛍光検査

従来型の加熱処理を施されたサファイアの多くは、短波(SW)紫外線下において白濁蛍光を示すことはよく知られている。これは、変成環境下で鉄が比較的低含有量のサファイアに特に当てはまる(スリランカ、ビルマ、マダガスカル、カシミール産)。HT+P処理サファイアはそれと似たような方法で加熱されており、出発材料も鉄が低含有の変成岩素材であることが多いため、我々は同様の蛍光反応を期待していたが、その通りであった。長波紫外線では、天然のあるいは通常の加熱処理サファイアとこれらのHT+P処理サファイアとの間に識別可能となるような違いは生じなかった。短波紫外線、UVでは従来型の加熱処理石と同様の反応が見られた。

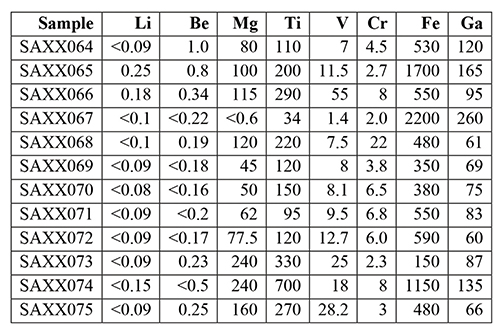

微量元素分析

GGLにおける12試料のLA–ICP–MS分析で検査したところ以下の結果が得られた(試料1石あたり3か所のレーザー スポット;単位ppm)。特に、リチウム、ベリリウム、チタンが拡散されている証拠は見られなかった。

紫外–可視–近赤外(UV–Vis–NIR)スペクトル

HT+P処理サファイアの紫外-可視-近赤外スペクトルを比較して、これらの処理石と、従来型の加熱処理サファイアおよび未処理のサファイアとの間には違いが見られないことが分かった。これは、それぞれのカテゴリーで発色因子(Fe2+–Ti4+の原子価間電荷移動)が同じであるため、当然である。

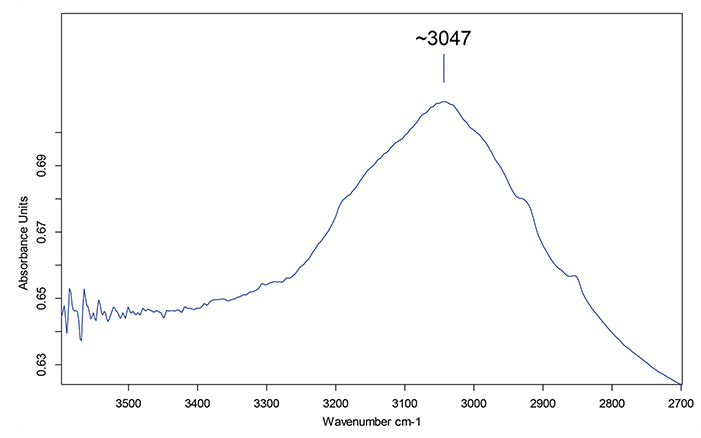

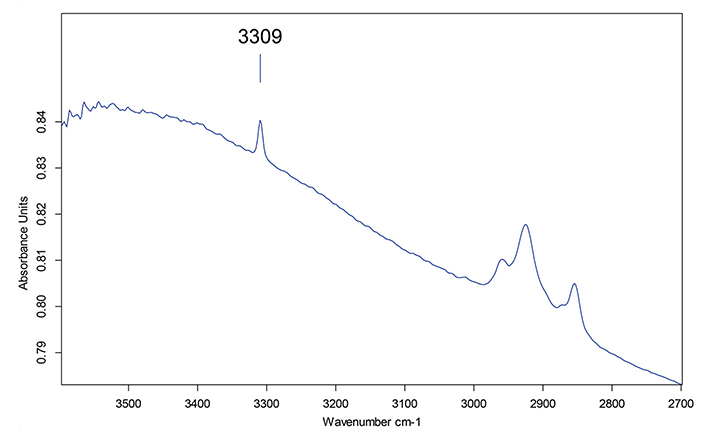

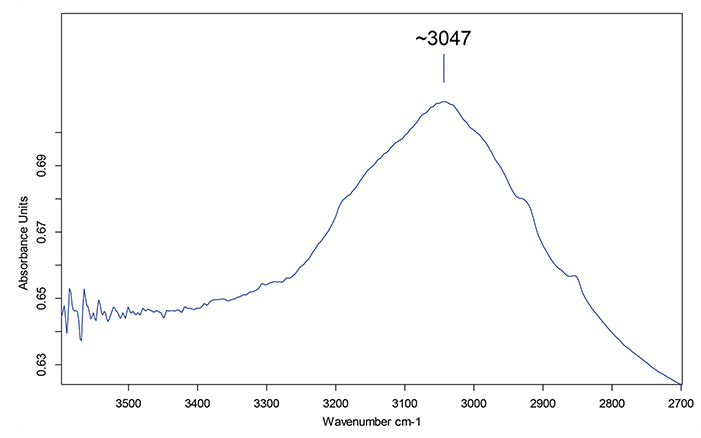

赤外(IR)スペクトル

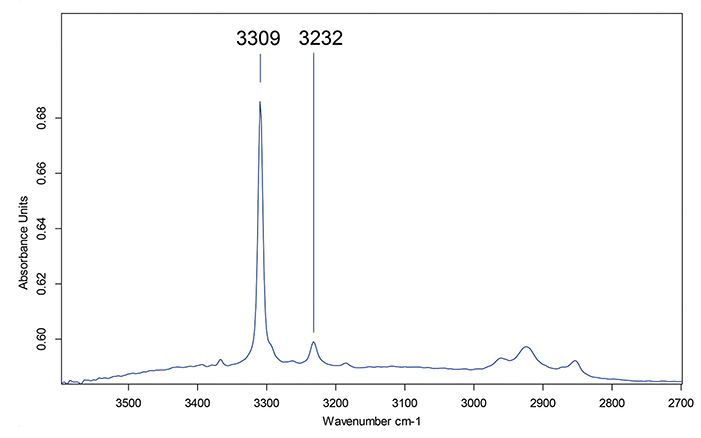

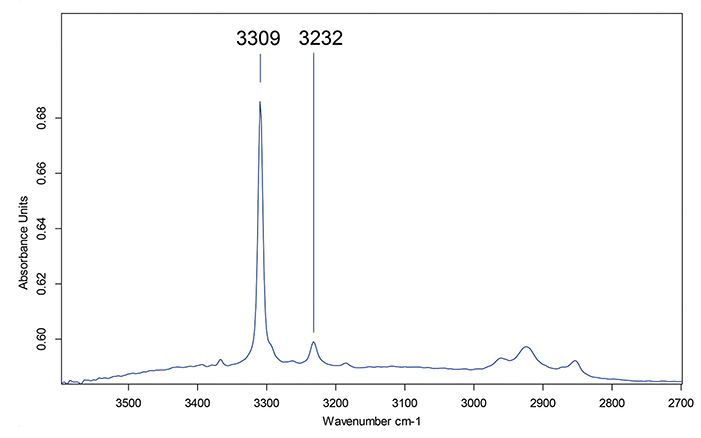

HT+P処理サファイアと伝統的な加熱処理サファイアとを識別することが可能なのは、赤外スペクトルである。HT+P処理サファイアの大半が、~3043㎝–1に幅広いピークを示す。

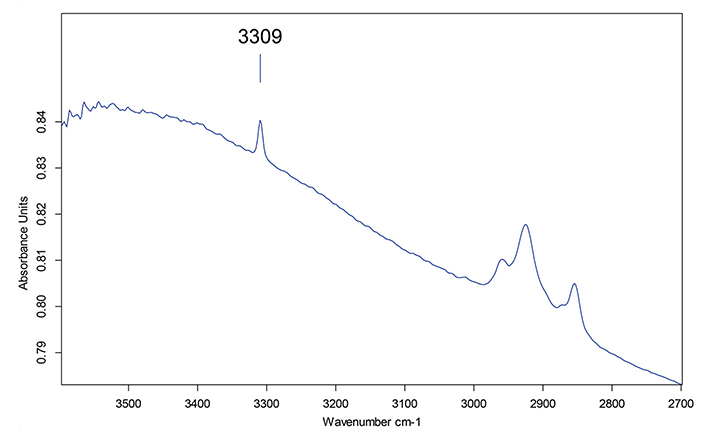

天然非加熱サファイア(およびルビー)は、通常3309㎝–1にピークを示す。その強度はまちまちである。それ以外の赤外スペクトルもみられるが、これが最も一般的にみられるタイプである。

処理及び天然のコランダムの赤外スペクトルのあらゆる変化について詳しく述べることは、今回の記事の目的の範囲外である。可能性は数十ほどもある。注目すべきなのは、およそ3047㎝–1の幅広いピークがその石にHT+P処理が施されていることを示唆するということである。しかし、このピークが見られなくても石がHT+P処理されている可能性ままだ大きく残されている。

鑑別のまとめ

HT+P処理サファイアの同定を、従来型の加熱処理サファイアと比較して以下のようにまとめる:

- 顕微鏡観察では明確な識別手段とはならない。良くてもせいぜい、一部のひび割れにおいて極めてわずかな違いが見られるだけである。

- 紫外線蛍光、UV–Vis–NIR吸収、そして微量元素組成は、この処理に対しての鑑別手段とはならない。

- FTIRスペクトルでは鑑別はできるが(一部のHT+P処理サファイアの〜3047㎝–1ピーク)、スペクトルはばらつきが大きく、~3047ピークはさらに加熱をすることで消失する。HT+P処理サファイアの多くは、この処理の看破にはならない赤外スペクトルを示す。

耐久検性査

前述したGRSの研究(Peretti et al., 2018, 2019)は、圧力を伴って高温処理されたサファイアの耐久性に関して起こりうる問題を2点報告している。

GRSの報告:

「HPHT処理サファイアのファセット エッジをペーパー クリップで削ってみたところ、ファセット エッジは細かく砕けた。耐久性の低下の明らかな証拠である。HPHT処理サファイアの表面を再研磨する際、宝石カッターは宝石が異常に熱くなったと報告している。さらに、ウエハーにするためにサファイアをソーイングする際、ある試料はソーイング工程の残り4分の1のところで砕けたことが判明した。

幾つかの工程を経たHPHT処理サファイア(従来型の加熱処理プラス、追加のHPHT処理)だけがこのような低い靭性を示すということは考えられる。しかし、この新しい処理方法が検出されている以上、すべての石にかなりの靭性の低下がみられることを予測しておくのが安全である。」

もちろんこれが本当なら、深刻な問題であり、処理石に対する耐久性検査には特別な注意を払う必要がある。今回の研究では、試料は3つのカテゴリーから選出した:

A. アイ クリーン(目に見えるインクルージョンがない)

B. インクルーデッド(インクルージョンがある)

C. ヘビリー インクルーデッド(インクルージョンが顕著に見える)

さらに、1石の試料は処理の後にファセット カットした。

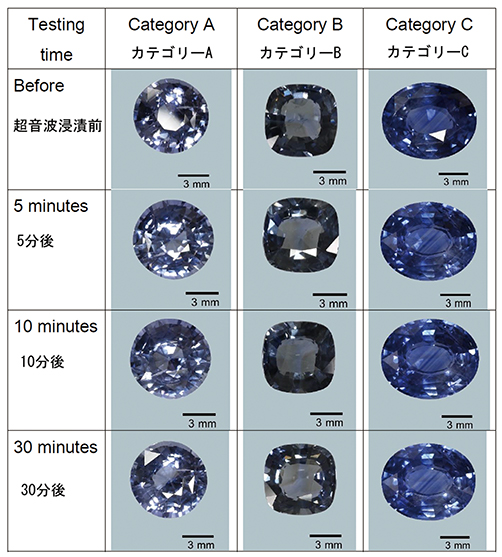

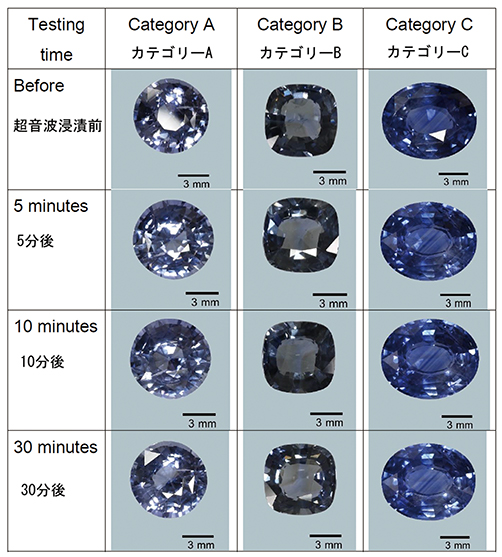

超音波クリーニング検査

超音波クリーニング容器を低温のぬるま湯で満たした。すべての試料をワイヤー籠に入れ、個々に5,10,30分と漬けた。GITで行ったこの検査からは、石のいずれにも全く損傷を生じないことが分かった。

GGLでも同様の設定を行い、顕微鏡観察では超音波浸漬後に既存の摩耗以外に新しく生まれた損傷は見られなかった。

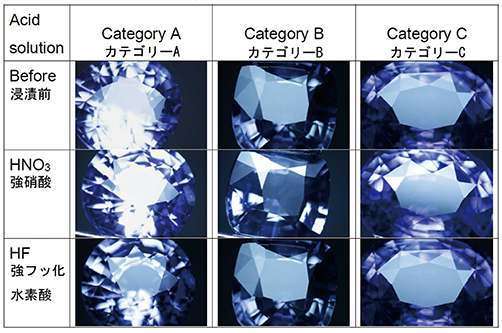

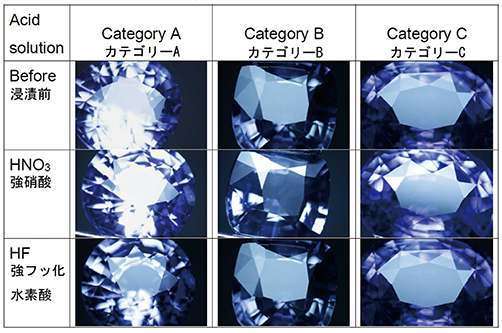

耐酸性検査

サファイア 試料を3石(各カテゴリーから1石)選び、以下の検査をした:

A. 強硝酸(HNO3)に6時間漬け…

B. 強フッ化水素酸(70%HF)に2分漬ける。

腐食やその他の損傷は生じなかった。

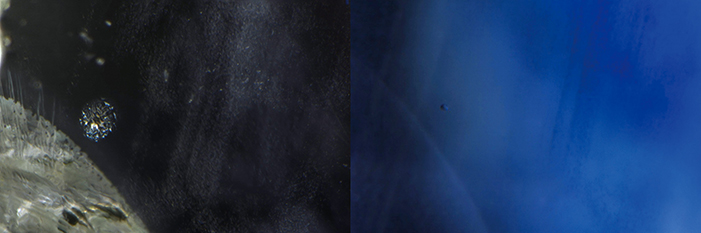

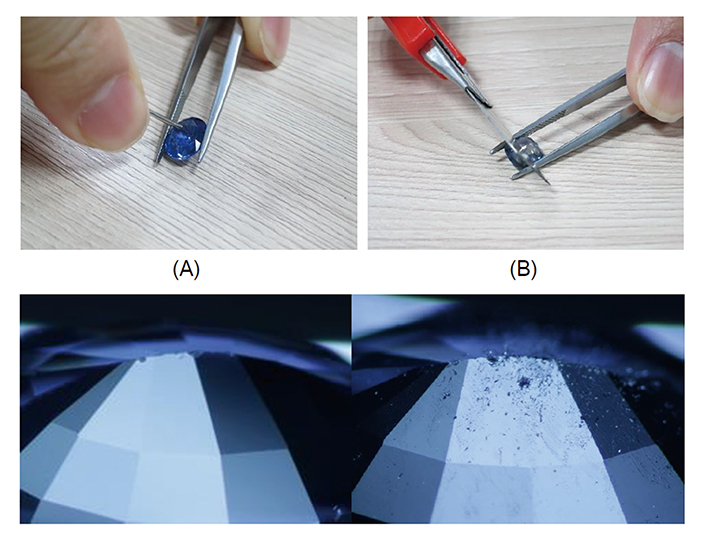

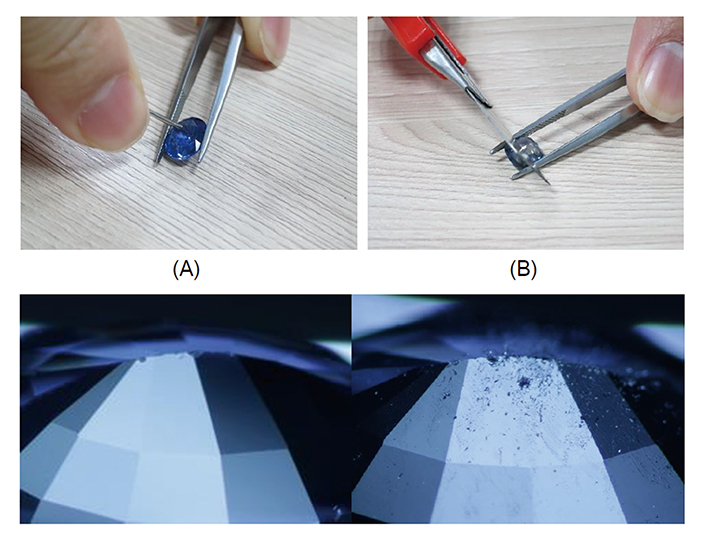

ペーパー クリップとスチール製の刃による靭性検査

試料を3石(各カテゴリーから1石)選び、ペーパー クリップ(A)とスチール製の刃(B)で傷をつける検査をした。石には何の損傷も生じず、ペーパー クリップから剥がれた金属の薄片がいくつも表面に蓄積していた。

GRSがペーパー クリップで傷をつけたと報告したサファイアはHT+P処理された石であるが、注意すべきはおそらく処理後に再研磨が施されていなかったということである。したがって、傷をつけたのは単にグラファイトの膜であってサファイア自体ではなかった可能性がある。

右:同じサファイアを最終研磨したところ。明らかに、ペーパー クリップではグラファイトの膜を引っ掻いたのだろうが、研磨後のサファイア自体には何の影響もない。写真:Imam Gems

落下試験

試料を3石(各カテゴリーから1石)選び、およそ1メートルの高さから硬いコンクリートの床に落とした。各石にこれを3回繰り返した。どの石にも何の損傷(ひび割れ)も見られなかった。

熱衝撃試験

試料を3石(各カテゴリーから1石)選び、ジュエラー用のトーチで石が赤色に発光するまで5秒間加熱した。この検査によって色の変化は生じなかった。カテゴリーCの1石(すでに顕著なインクルージョンが見られたもの)は、内部インクルージョンから伸展した新しい応力クラックを複数生じた。これは、処理の有無を問わず顕著にインクルージョンを含むサファイアでは、どの石にも予測されることである。

再研磨

GIA参照試料コレクションからのモンタナ産サファイアを韓国で圧力をかけて加熱し、その後ファセット カットした。研磨・カット工程では何の損傷も生じなかった。

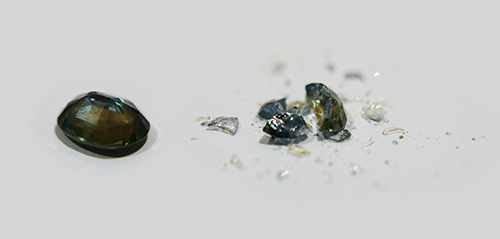

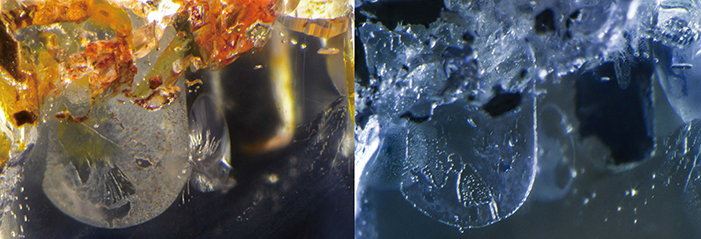

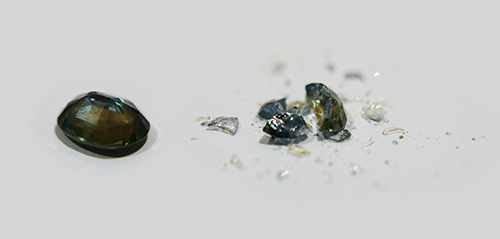

ハンマー試験

GRSの報告では、「ハンマー試験」を行って3つに砕けた石の写真を載せていた。その報告にはこうあった:

〔この写真からは〕ハンマーの衝撃によるストレス試験を受けたカボション石が3つの小片に砕け、石の中央に向かって放射状に広がる新しいひび割れを伴った三角形の破片。

このことを確かめるため、SSEFは従来型の加熱処理を施した玄武岩起源のサファイアを用いた。結果は下の写真の通り:

耐久性問題のまとめ

HT+P処理サファイアの脆弱性/耐久性問題に関する主張は、数か所のラボで同時に行った我々の検査では立証することができなかった。しかしそれらの検査からは、顕著にインクルージョンを含む(低品質の)出発原料に応力を与えると、加熱処理された方法(従来型か新しい方法か)にかかわらずひびや割れを生じることがある(耐久性問題)ことが分かった。

加熱処理されたものに限らず、すべてのサファイアがある程度の脆さを持っていることを覚えておく必要がある。著名なイギリスのジェモロジストであるロバート ウェブスターが1962年にその代表作Gemsに次のように記している:

「その硬度にもかかわらず、ルビーとサファイアはある程度の注意を以って扱うべきである。これらの石は僅かに脆さを孕んでいて、硬い表面に落としてしまったり強い衝撃を与えてしまうと、内部のひびや割れを引き起こす傾向があるからだ。」

Robert Webster, Gems 1962

HT+P処理サファイアに関する質問

Q. この処理が原因となる耐久性の問題はあるか?

A. 我々の研究からは、皆無であった。

Q. 処理により、クラリティの改良(ひび割れ修復、など)の点において大きな利点が生じるのか?

A. 我々が観察した違いは概してわずかであり、この点は伝統的に高温で加熱されるサファイアとは違っている。

Q. この処理により、市場に流通するサファイアの量が大きく増えるか?

A. 今のところ、それはない。

Q. 現在、この処理が施された石の何%がラボで看破できるか?

A. HT+P処理サファイアの多くは従来型の加熱処理された石と識別することができないため、それは不明である。

Q. この処理は単に加熱のみでなく個別の情報開示を当然必要とするのか?

A. 現在得られる情報に基づいて、必要ないと我々は考える。しかし、今後さらなる情報が明らかになった場合には状況が変わる可能性はある。

まとめ

AGTAはAGTAニュースの“Industry Gemstone Advisory”(AGTA , 2018)の中で以下のように述べている:

この新しい処理はサファイアの見かけの品質を改良するものであり、よってジュエリー業界に向けた連邦取引委員会(FTC)ガイドラインと、AGTAの処理情報開示に関する倫理要綱の両方の対象となっている。そのため、この新しい処理は、書面により、売り手から買い手に対して、圧力および加熱の処理として次のAGTA情報開示コード: 「HP」を付けて情報開示がなされなければならない。

我々は、業界は新しい処理が出現した際にそれが重要な違いを持っている場合にのみ新しい処理のカテゴリーを作るという事実を文書化してきた。これは以下の場合に当てはまる:

- 外部から内部に向かっての発色因子の拡散(Be、Cr、Ti拡散)

- 顕著にひび割れが修復した場合(モンスールビーのフラックスによる修復、など)。

HT+P処理サファイアでは、このどちらも見られなかった。さらに、GRSが指摘した耐久性の問題は我々の検査では再現することができなかった。我々は、この処理が加熱だけでは達成しえない何らかの結果を生じるという証拠を発見することはできなかった。その結果、この処理は石が加熱されていると宣言すること以上に特別の情報開示は必要ないと考える。

参考文献

- AGTA (n.d.) AGTA Gemstone Information Manual. American Gem Trade Association, 15th edition.

- AGTA (2018) AGTA Industry Gemstone Advisory [concerning sapphire heated with high temperatures and low pressures]. American Gem Trade Association, 8 December 2018.

- Anonymous (1916) Sapphire–mining industry of Anakie, Queensland. Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, Vol. 14, April–June, pp. 253–261.

- Beruni, M.i.A., al– (1989) The Book Most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: al–Beruni’s Book on Mineralogy [Kitab al–jamahir fi marifat al–jawahir]. Trans. by Said, H.M., One Hundred Great Books of Islamic Civilization, Natural Sciences No. 66, Islamabad, Pakistan Hijra Council, 355 pp.

- Choi H.M., Kim S.K. and Kim Y.C. (2014a) Appearance of new treatment method on sapphire using HPHT apparatus. ICGL Newsletter, No. 4, pp. 1–2.

- Choi H.–M., Kim S.–K. and Kim Y.C. (2014b) New treated blue sapphire by HPHT apparatus. Proceedings of the 4th International Gem and Jewelry Conference (GIT2014), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 8–9 December, pp. 104–105.

- Choi H., Kim S., Kim Y., Leelawatanasuk T., Lhuaumporn T., Atsawatanapirom N., Ounorn P. (2018) Sri Lankan sapphire enhanced by heat with pressure. Journal of The Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, Vol. 39, pp. 16–25.

- Crowningshield, R. (1966) Developments and Highlights at the Gem Trade Lab in New York: Unusual items encountered [sapphire with unusual fluorescence]. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 12, No. 3, Fall, p. 73.

- Hughes, R.W. and Galibert, O. (1998) Foreign affairs: Fracture healing/filling of Möng Hsu ruby. Australian Gemmologist, Vol. 20, No. 2, April–June, pp. 70–74.

- Emmett, J.L., Scarratt, K. et al. (2003) Beryllium diffusion of ruby and sapphire. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 39, No. 2, Summer, pp. 84–135.

- Hughes, R.W. and Emmett, J.L. (2004) Fluxed up: The fracture healing of ruby. The Guide, Vol. 23, Issue 5, Part 1, Sept.–Oct., pp. 1, 4–9.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. & Hughes, E.B. (2014) Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector’s Guide. GIT, Bangkok, 384 pp.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. & Hughes, E.B. (2017) Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist’s Guide. Lotus Publishing, Bangkok, 816 pp.

- Keller, P.C. (1982) The Chanthaburi–Trat gem field, Thailand. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 18, No. 4, Winter, pp. 186–196.

- Kim, S.–K., Choi, H.–M., Kim, Y.–C., Wathanakul, P., Leelawatanasuk, T., Atsawatanapirom, N., Ounorn, P. and Lhuaamporn, T. (2016) Gem Notes: HPHT–treated blue sapphire: An update. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 35, No. 3, July, pp. 208–210.

- Nassau, K. (1981) Heat treating ruby and sapphire: Technical aspects. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 17, No. 3, Fall, pp. 121–131.

- Peretti, A., Musa, M., Bieri, W., Cleveland, E., Ahamed, I., Mattias, A., & Hahn, L. (2018, 2019) Identification and characteristics of PHT (‘HPHT’)–treated sapphires: An update of the GRS research progress. GemResearch SwissLab, online report, first posted 12 November 2018; updated 15 January 2019; first accessed 12 November 2018.

- Song, J. Noh, Y., and Song, O., 2015. Color enhancement of natural sapphires by high pressure high–temperature process, Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 165–170.

注:文献をさらに詳しく読みたい方は、Lotus Gemologyの参照データベース:Four Treasure(http://www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/library/reference-database)をご覧ください。

============================

============================

This is the article published at www.lotusgemology.com. Posted here with permission. Originally presented at the Gemstone Industry & Laboratory Conference (GILC) in Tucson on 4th February 2019.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Squeezing Sapphire: Corundum treated with high temperatures and low pressure (HT+P)

26 February 2019: Sapphires heated with high temperatures and low pressures (~1kbar) first entered the market in 2009, becoming more common since 2016. This article examines the process in detail and looks at the question of whether a separate disclosure is needed for the treatment.

The following organizations have contributed to and endorse the contents of this article: CGL Central Gem Lab, Japan; CISGEM, Italy; German Gem Lab (DSEF), Germany; Dunaigre Consulting, Switzerland; Gemological Institute of America (GIA), USA; Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand (GIT); GJEPC–GTL, India; Gübelin Gem Lab, Switzerland; Hanmi Lab, South Korea; ICA Lab, Thailand; Lotus Gemology, Thailand; Swiss Gemmological Institute (SSEF), Switzerland.

Discussion

Sapphires heated with high temperatures and low pressures (~1kbar; hereafter referred to as HT+P sapphire) first entered the market in 2009, becoming more common since 2016. In late 2018, GemResearchSwisslab (GRS) issued a study claiming that such stones had durability issues (Peretti et al., 2018, 2019). This was quickly followed up by a press release from the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA, 2018) stating that they would require separate disclosure of any sapphires treated with heat and pressure, under the category of HP. The AGTA also noted that, like all treatments, any documents going to the consumer would require not just codes, but “clear language” disclosure (e.g. sapphire treated with heat and pressure).

While the AGTA’s stated reason for a different disclosure was beacuse the treatment changed the quality of the stones, they sidestepped the issue that the treatment was already being “disclosed,” just not with a different category. We believe one must ask if the changes produced by the HT+P treatment are something beyond what one could do with traditional heating? This article is an attempt to address the central question of whether or not the addition of modest pressure to the heat treatment process deserves separate disclosure to traders and consumers.

Timeline: A history of heat

In order to provide perspective on the pressure heating of sapphires in respect to other processes, we believe it is useful to review the history of corundum heat treatment.

circa 1045 AD: Low temperatures to remove blue tints from ruby/pink sapphire

The great polymath, al Beruni (b. 973; d. 1050 AD) describes the process of heating ruby in a furnace designed to melt 50 mithqals (212 grams) of gold. Since gold melts at 1064°C, we know the furnace was capable of reaching temperatures of 1100°C or greater, in air. We also know that this process is effective, as it is essentially what treaters do today to these types of ruby and pink/purple sapphire. (Beruni, 1989; Hughes et al., 2017). See also Early Heat Treatment(www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/lab/enhancements#gemtreatments).

1916: Low temperature (800–1200°C) heating to lighten blues

Heat treatment at low temperatures of dark blue (basaltic) sapphires from Queensland (Australia) to lighten their color. This process is later adapted for heating all dark blue sapphires and continues to this day. It is difficult to detect, as these stones have already experienced natural heating within the basaltic magma during their journey to the Earth’s surface (Anonymous, 1916).

1966: Higher temperatures

The GIA’s Robert Crowningshield reports on a sapphire that was reportedly from Thailand and yet displayed a weak iron spectrum and showed an unusual chalky short-wave ultraviolet fluorescence. We now know this fluorescence is commonly associated with high–temperature heating of geuda–type metamorphic sapphire (Crowningshield, 1966). Knowing what we know now, this appears to have been an early attempt at high–temperature heating of a low–iron metamorphic sapphire.

circa 1975: Enter the geuda

Diesel furnaces (1500°C+) are used to convert Sri Lankan geuda sapphires to blue. Addition of oxygen produces the higher temperatures needed to dissolve rutile. The process in most cases involves hydrogen diffusion in a reducing atmosphere. By the late 1970’s the material flooded the market, with many buyers having no idea that they had been buying heated stones. Thus, in the 1980‟s the trade blessed it as “traditional” heat treatment, even though the “tradition” then dated less than 20 years and was radically different from what had come before. New York’s American Gemological Laboratories (AGL) was the first lab to begin disclosing this treatment; it was not until the late 1980’s that other labs followed.

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? No.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Sometimes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? No.

1980: Titanium lattice diffusion

Entry of titanium lattice-diffused (then known as ‘surface diffused’) sapphires into the market. Although they are initially sold without proper disclosure by a major Swiss company that had bought the patent rights for the process from Union Carbide Corp., they are quickly identified and achieve little market penetration (Nassau, 1981).

- Was it a new treatment? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? Yes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? Yes.

Early 1980’s: Electric furnaces

Electric muffle furnaces are introduced, allowing better control over atmosphere and temperature; oxidizing atmospheres convert many Sri Lankan sapphires from pale blue to vivid yellow and orange and this material floods the market (Keller, 1982).

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? No.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? No.

Mid 1980’s: Flux healing

Additions of flux during heating produce fissure healing, where cracked stones are healed shut with submicroscopic amounts of synthetic corundum. When ruby is discovered at Mong Hsu in 1991, this material floods the market (Hughes et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2004).

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? No.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Yes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? Yes.

Mid 1990’s–2001: Beryllium diffusion

Beryllium diffused corundums slowly infiltrate the market. The process is later sold, resulting in a flood of material by the year 2001. Gemologists identify the cause in early 2002 (Emmett et al., 2003).

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? Yes.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Yes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? Yes.

Top: Sri Lankan geuda sapphire before (left) and after (right) high-temperature (1500°C+) heating.

Below: Madagascar sapphire before (left) and after (right) high–temperature (1700°C+) heating with beryllium (Be). Geuda heat treatment requires only that it be disclosed as heat (H), while Be diffusion requires special disclosure because a chromophore (Be) is inserted into the stone from outside and also because the recutting of some stones may result in loss of color. From Hughes et al., 2014. Photos: Wimon Manorotkul; specimens and heating: John Emmett.

2000–2003: Longer heating times, more sophisticated regimens

Longer heating times allow treaters to better dial in the finished color. Treaters undertake extensive experiments to improve their processes, culminating in the “Punsiri” crisis, where a Sri Lankan treater’s stones were initially suspected of being a potential problem, but were later shown to be just a sophisticated variation on standard heat treatment.

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? No.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Sometimes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? No.

2003: Beryllium diffusion to lighten dark blue sapphire

Diffusion of beryllium into blue sapphire to lighten the color. This material slowly infiltrates the market as it requires sophisticated equipment to identify (Emmett et al., 2003).

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? Yes.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Sometimes.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? Yes.

2009–present: Sapphires heated with pressure (HT+P)

Entry of blue sapphire treated by pressure plus high-temperature heat (Choi et al., 2014a, b). These stones started to appear slowly in the market. Currently

- Is it a modification of an earlier process? Yes.

- Does it insert chromophores from outside? No.

- Does it recrystallize/heal significant fissures of the stone? Sometimes.

- Does it have durability problems? Not from what we can see.

- Is separate disclosure (beyond ‘heat’) now required? This is the burning question.

From the above it is clear that the gem trade’s record on treatment disclosure has been uneven, at best, and was often based on the market penetration of the treated material prior to its identification by gemologists. When market penetration was high (high–temperature heating of geuda sapphires), the trade tended to “grandfather” it as “traditional”; where a treatment was caught early (beryllium diffusion), the trade was more critical. This is not unexpected or unusual. Humans look out for their own interests first.

That said, the current standards, according to the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) guidelines and the AGTA disclosure policies, are as follows (AGTA, n.d.):

Treatment details must be disclosed when…

- The treatment is not permanent and its effects are lost over time; or

- The treatment creates special care requirements for the gemstone to retain the benefit of the treatment; or

- The treatment has a significant effect on the value of the gemstone.

In regard to the new high heat + low pressure (HT+P) treatment, are any of the above disclosure conditions met? These are important questions that this article will attempt to answer.

Under pressure

Diamond treaters have been using high temperatures and high pressures to improve color since the 1990’s. Thus it was only a matter of time that corundum cookers would look at using pressure in the heat treatment of ruby & sapphire. Indeed, starting in 1997, the German Furnace company LINN offered autoclaves with low pressure for sale for

corundum treatment (up to 25 bar). Several of these were sold to Asia. Similarly, those involved in heating tourmaline have long used pressure heating to produce changes in color without causing the explosion of fluid–filled negative crystals. The treatment (temperatures less than 700°C; pressure 0.5–1.5 kbar) continues to this day and is basically undetectable.

When it comes to the HT+P treatment of sapphire, the pressures used (~1kbar) are much lower. Compared with the pressures that sapphires grow under in the ground, the treatment pressures are nowhere near enough to prevent the rupture of fluid-filled negative crystals in the gem. Indeed, the sapphires that are used in this treatment are often stones that have been previously heated at high temperatures. This brings up the question: why is the HT+P treatment being used? The answer is that it is far quicker, allowing stones to be treated in 30 minutes or less.

But there are disadvantages, too. The heating apparatus is far more expensive than typical treatment ovens. And in most cases, only one stone can be treated at a time. In addition, the phase change that produces the change of color occurs so rapidly that it is more difficult to control. This is one reason why the treatment has produced such mixed results.

Squeezing sapphire: The HT+P treatment methodology

The following information is based largely on visits to the heating facility in South Korea by Hanmi Lab, GIT Thailand, and GIA.

Starting material used for HT+P treatment

工場で処理されるサファイア。写真:Shane McClure、GIA

Parcel of sapphires for treatment at the factory. Photo: Shane McClure, GIA.

Bottom: The same sapphires after HT+P treatment. As with conventional treatments, results vary according to the chemical makeup of the starting material. From Choi et al., 2018. Photos by P. Ounorn.conventional treatments, results vary according to the chemical makeup of the starting material. From Choi et al., 2018. Photos by P. Ounorn.

Identification of HT+P treated sapphire Inclusions

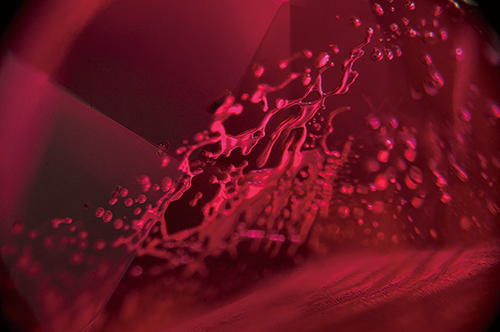

Pressure–heated sapphire before (left) and after (right) treatment. In this case, after heating with pressure the iron staining was gone, while the fissure in the middle partially healed, but was still quite visible. Photos: GIA.

Summary of microscopic observations of HT+P sapphire

The features observed in HT+P sapphires were similar to those in “traditionally” high-temperature heated sapphires.

- Subtle differences were found in surface granularity of healed fissures. But similar features can also be seen in conventionally heated sapphires.

- Sometimes graphite accumulations were seen in fissures and cavities close to the surface (remnants of the graphite filled crucible).

In most cases, microscopic observations did not provide sufficient evidence to separate this treatment from ordinary heat treatments. From the above images, we can see that the types of changes resulting from the treatment were virtually identical with what one could expect from high temperature heat treatment without pressure.

Other tests

A number of other gemological tests were performed on HT+P-treated sapphires. These included…

Ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence

It is well known that many sapphires treated by traditional heat treatment will show a chalky fluorescence under shortwave (SW) ultraviolet light. This is particularly true of sapphires from metamorphic environments with relative low iron contents (such as Sri Lanka, Burma, Madagascar, and Kashmir). Since HT+P–treated sapphires are heated in a similar way and the starting material tends to be low iron metamorphic material, we would expect similar reactions and this is what we found. Long wave UV did not produce any diagnostic difference between natural or normally heated sapphires and those treated by the HT+P process. SW UV produced reactions similar to traditionally heated stones.

Trace element analysis

LA–ICP–MS tests on 12 samples from GGL gave the following results (average of three laser spots per sample; in ppm). Specifically, there was no evidence of diffusion of lithium, beryllium or titanium.

UV-Vis-NIR spectrum

Comparison of the UV–Vis–NIR spectra of HT+P sapphires showed no differences between them and sapphires subjected to traditional heat treatment, or untreated sapphires. This is not surprising as the chromophore of each (intervalence charge transfer of Fe2+–Ti4+) is the same.

Infrared (IR) spectrum

The one area where it is possible to separate HT+P sapphires from those heated by traditional methods is with the infrared spectrum. A significant percentage of HT+P stones display a broad peak at ~3047 cm–1.

Natural untreated sapphire (and ruby) typically shows a peak at 3309 cm–1. It can be of varying intensities. Other IR spectra are also possible, but this is the most common type.

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail all the variations in IR spectra of corundum, treated and natural. There are dozens of possibilities. What is important to note is that the broad peak at about 3047 cm–1 suggests the stone is HT+P treated. However, the absence of that peak still leaves open a significant chance that the stone is HT+P treated.

Identification summary

The identification of HT+P treated sapphire can be summarized as follows, compared to traditionally heated sapphire:

- The microscope provides no clear–cut means of separation. At best, extremely subtle differences are seen in some fissures.

- Ultraviolet fluorescence, UV–Vis–NIR absorption, and trace element composition are not diagnostic for the treatment.

- While FTIR spectra can be diagnostic (3047 peak in some HT+P treated sapphires), the spectra are quite variable and the 3047 peak can even be removed with further heating. Many HT+P sapphires show IR spectra that are not diagnostic for the treatment.

Durability studies

The previously mentioned GRS study (Peretti et al., 2018, 2019) had reported two possible issues with durability on sapphires treated with high temperatures and pressure.

GRS reported:

“When we tried to scratch a facet edge of a HPHT–treated sapphire with a paper clip, the facet edges crumbled. A clear indication of reduced durability. When re–polishing the surfaces of HPHT–treated sapphires, the cutter reported that the stones got unusually hot. Further, when sawing the sapphires to produce wafers, we noticed certain samples were breaking off the last quarter of the sawing path.”

“It is possible that only multi–step HPHT–treated sapphires (conventional heating plus additional HPHT–treatment) show this type of brittleness. However, it is safer to assume a higher degree of brittleness for all stones, once this new treatment method is detected.”

Obviously if true, this is a serious problem, and so particular attention was paid to durability testing of the treated stones. For this study, samples were chosen from three categories:

A. Eye clean

B. Included

C. Heavily included

In addition, one sample was faceted after treatment.

Ultrasonic cleaning

An ultrasonic bath was filled with slightly warm water. All samples were placed on a wire bucket and soaked for 5, 10, and 30 minutes respectively. The test at GIT revealed no damage on any of the stones.

A similar setup was chosen at GGL for four sapphires revealing by microscopic inspection no additional damage on top of the pre-existent abrasions after the ultrasonic bath.

Acid resistance

Three sapphire samples (one of each category) were selected for: A. Soaking in strong nitric acid (HNO3) for six hours and…

B. Soaking in strong hydrofluoric acid (70% HF) for two minutes. No etching or other damage occurred.

Brittleness testing with paper clip and steel blade

Three stones (one of each category) were selected to be scratched by a paper clip (A) and cutter blade (B). We observed no damage to the stones, only flakes of metal that came off the paper clip and accumulated on the surface.

It should be noted that the specimen that GRS reported that they scratched with a paper clip was a stone that had been HT+P treated, but which had probably not been repolished following the treatment. Thus it is likely that they were simply scratching the graphite crust, not the sapphire itself.

Right: The same sapphire after final polishing. Obviously, a paper clip could scratch the graphite crust, but it would have no impact on the sapphire after polishing. Photos: Imam Gems. Click on the photos for larger images.

Drop testing

Three stones (one of each category) were selected and dropped onto a hard concrete floor from approximately one meter height. This procedure was repeated three times for each stone. No damage (cracking) was observed in any of the samples.

Resistance to thermal shock

Three stones (one of each category) were selected and heated with a jeweler’s torch for five seconds until each of them started to glow red. No change of color occurred due to the testing. One stone from category C (which was already highly included) developed additional tension cracks extending from internal inclusions. This is to be expected from any highly included sapphire, treated or not.

Repolishing

A Montana sapphire from the GIA reference collection was heated with pressure in South Korea and subsequently faceted. No damage occurred during polishing and cutting.

Hammer test

In the GRS report, they showed a photo of a sapphire that had been subjected to a “hammer test” and had broken into three pieces. Quoting from their report:

[This photo shows] three fragments of a stress tested cabochon impacted by hammer created triangular fragments with newly formed cracks radiating toward the center of the stone.

To test this claim, SSEF subjected a basalt-related sapphire that had undergone traditional heat treatment. The results are shown in the photo below:

Summary of durability issues

The claims of brittleness/durability problems of HT+P treated sapphires could not be substantiated by our tests, which were carried out by several laboratories simultaneously. But they did reveal that subjecting heavily included starting material (low quality) to stress may produce fissures and cracks (durability issue), regardless of which heating method (‘traditional’ or ‘new’) is applied.

We should remember that all sapphire, not just stones subjected to heat treatment, have a degree of brittleness. As the famous British gemologist Robert Webster wrote in his 1962 magnum opus Gems:

“Despite their hardness, ruby and sapphire need to be handled with some care, for they are to a slight extent brittle and if dropped on a hard surface or given a sharp blow tend to develop internal flaws and cracks.”

Robert Webster, Gems 1962

Questions regarding HT+P treated sapphires

Q. Are there durability problems that result from this treatment?

A. Our studies revealed none.

Q. Does treatment produce significant advantages in terms of improvements in clarity (fissure healing, etc.)?

A. The differences we have seen are generally slight and not unlike sapphires conventionally heated at high temperatures.

Q. Does this treatment significantly increase the supply of sapphire in the market?

A. To date, it has not.

Q. What percentage of stones that have been subjected to this treatment are currently identifiable by labs?

A. We simply do not know because many HT+P treated sapphires cannot be separated from traditionally heated stones.

Q. Does this treatment warrant separate disclosure beyond just heat?

A. Based on our current information, we believe it does not. But this could change if further information comes to light.

Summary

In their Industry Advisory (AGTA, 2018), the AGTA stated the following:

This new treatment does improve the apparent quality of the sapphire and as such is subject to both Federal Trade Commission Guides for the jewelry industry and the AGTA’s Code of Ethics about treatment disclosure. For that reason, this new treatment must be disclosed, in writing, by the seller to the buyer as pressure and heat treatment with the following AGTA Disclosure Code: HP

We have clearly documented the fact that the trade only creates new categories of treatments when there are specific significant differences in a new treatment. This would apply to:

- Outside-in diffusion of chromophores (Be, Cr & Ti diffusion)

- Significant healing of fissures (flux healing of Mong Hsu ruby, etc.)

With HT+P treated sapphires, we do not find either of these things. In addition, the durability problems cited by GRS could not be duplicated in our tests. We have found no evidence that this treatment does anything that could not be done with heat alone. As a result, we believe this treatment should not require specific disclosure beyond declaring the stones as heated.

References

- AGTA (n.d.) AGTA Gemstone Information Manual. American Gem Trade Association, 15th edition.

- AGTA (2018) AGTA Industry Gemstone Advisory [concerning sapphire heated with high temperatures and lowpressures]. American Gem Trade Association, 8 December 2018.

- Anonymous (1916) Sapphire-mining industry of Anakie, Queensland. Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, Vol. 14,April–June, pp. 253–261.

- Beruni, M.i.A., al– (1989) The Book Most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: al–Beruni’s Book onMineralogy [Kitab al–jamahir fi marifat al–jawahir]. Trans. by Said, H.M., One Hundred Great Books of IslamicCivilization, Natural Sciences No. 66, Islamabad, Pakistan Hijra Council, 355 pp.

- Choi H.M., Kim S.K. and Kim Y.C. (2014a) Appearance of new treatment method on sapphire using HPHT apparatus. ICGL Newsletter, No. 4, pp. 1–2.

- Choi H.–M., Kim S.–K. and Kim Y.C. (2014b) New treated blue sapphire by HPHT apparatus. Proceedings of the 4thInternational Gem and Jewelry Conference (GIT2014), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 8–9 December, pp. 104–105.

- Choi H., Kim S., Kim Y., Leelawatanasuk T., Lhuaumporn T., Atsawatanapirom N., Ounorn P. (2018) Sri Lankansapphire enhanced by heat with pressure. Journal of The Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, Vol. 39, pp. 16–25.

- Crowningshield, R. (1966) Developments and Highlights at the Gem Trade Lab in New York: Unusual itemsencountered [sapphire with unusual fluorescence]. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 12, No. 3, Fall, p. 73.

- Hughes, R.W. and Galibert, O. (1998) Foreign affairs: Fracture healing/filling of Möng Hsu ruby. AustralianGemmologist, Vol. 20, No. 2, April–June, pp. 70–74.

- Emmett, J.L., Scarratt, K. et al. (2003) Beryllium diffusion of ruby and sapphire. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 39, No. 2, Summer, pp. 84–135.

- Hughes, R.W. and Emmett, J.L. (2004) Fluxed up: The fracture healing of ruby. The Guide, Vol. 23, Issue 5, Part 1, Sept.–Oct., pp. 1, 4–9.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. & Hughes, E.B. (2014) Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector’s Guide. GIT, Bangkok, 384 pp.

- Hughes, R.W., Manorotkul, W. & Hughes, E.B. (2017) Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist’s Guide. Lotus Publishing, Bangkok, 816 pp.

- Keller, P.C. (1982) The Chanthaburi–Trat gem field, Thailand. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 18, No. 4, Winter, pp. 186– 196.

- Kim, S.-K., Choi, H.-M., Kim, Y.–C., Wathanakul, P., Leelawatanasuk, T., Atsawatanapirom, N., Ounorn, P. and Lhuaamporn, T. (2016) Gem Notes: HPHT–treated blue sapphire: An update. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 35, No. 3, July, pp. 208–210.

- Nassau, K. (1981) Heat treating ruby and sapphire: Technical aspects. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 17, No. 3, Fall, pp. 121–131.

- Peretti, A., Musa, M., Bieri, W., Cleveland, E., Ahamed, I., Mattias, A., & Hahn, L. (2018, 2019) Identification and characteristics of PHT („HPHT‟)–treated sapphires: An update of the GRS research progress. GemResearch SwissLab, online report, first posted 12 November 2018; updated 15 January 2019; first accessed 12 November 2018.

- Song, J. Noh, Y., and Song, O., 2015. Color enhancement of natural sapphires by high pressure high–temperature process, Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 165–170.

Note: For those who wish to explore the literature further, see Four Treasures: Lotus Gemology’s Reference Database.